Witney and the Industrial Revolution

A young woman weaver next to her loom, Witney, early 20th

century.

The introduction of machinery

The first sign of the Industrial Revolution in Witney was the introduction of a horse-powered 'rowing machine' for raising the nap on blankets in 1782 [1]. It was purchased by the Witney Blanket Weavers' Company (the local trade guild), with members of the Company paying a fee for using it. Elsewhere in Britain the introduction of machinery often sparked riots and attacks on equipment by those who feared it would take away their livelihoods; the fact that the rowing machine was available to all members of the Company may explain why it was accepted without opposition from local workers.

Flying shuttle for a handloom - the rollers underneath helped

the weaver send it flying across the wide blanket looms.

Water-powered spinning machinery was introduced to Witney by Edmund Wright at New Mill in the first decade of the 19th century. Unfortunately he was killed in 1808 when he fell into his own mill wheel, much to the delight of local hand spinners who resented having their livelihoods taken away. The Earlys then took over New Mill and invested heavily in developing it as a spinning mill: when it burned down in 1818 it was recorded that over £10,000 of damage was done, much of it to new spinning equipment, a huge sum for the times. In August of that year, after the fire, John Early visited towns in Lancashire and Yorkshire to study the new industrial methods and purchase modern replacement equipment: he bought £308 of carding equipment for New Mill [4]. Spinning machinery was improved throughout the first half of the century, and fully automatic spinning mules were installed at New Mill by Charles Early in 1853 [5].

Although the flying shuttle had actually increased the blanket trade in Witney, the effect of this new spinning equipment was disastrous for the many families who relied on hand spinning as a source of extra income. The effects were felt over a large area: in 1826 William Cobbett described the village of Withington in Gloucestershire, 23 miles from Witney, as dilapidated and shabby even though a few years previously it had been a prosperous place; he attributed a large part of this decline to the use of spinning machinery in Witney. A Witney historian writing in 1852 also recorded that forty years previously 'large numbers of people were altogether thrown out of employment' by the new machinery [6].

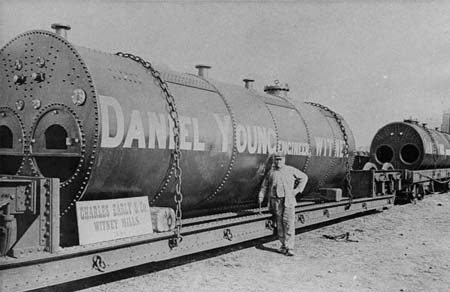

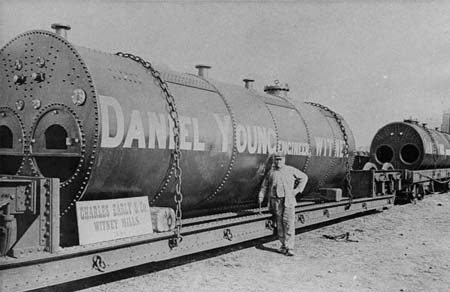

Daniel Young, engineer, with new boilers delivered by train and

destined for Witney Mill, late 19th century.

Young girl in the weaving shed at Witney Mill rewinding

unravelled power loom bobbins by hand.

The introduction of the power loom was the last major development in the transformation of the Witney blanket industry from a cottage industry to a factory system. Even so, outworkers continued to be used for many years [12], and handlooms continued to be used for some products such as horse collar check right up until the 1960s. Handlooms were just as fast as power looms for collar check because the shuttle had to be changed frequently to weave different colours into the cloth.

How did Witney survive the competition?

The greatest period of change in the Witney blanket industry took place between 1800 and 1840, when it went from being a cottage industry to a factory-based system [13]. By the time the inspectors of the Assistant Hand-loom Weavers Commission arrived in 1838, there were only six major manufacturers in the town employing ten weavers or more and about the same number employing six weavers or less; 'factory weavers' were mentioned. The majority of these changes took place well in advance of the introduction of power looms; why was this?

The Witney industry had an excellent and long established reputation for making high quality products and this helped the manufacturers secure large contracts even in the face of cheaper competition. They had over the years, aided by the Blanket Weavers' Company, built up excellent trade contacts and were not content with trying to supply just their traditional markets but secured new opportunities, especially in North America through the Hudson's Bay Company.

The industry was also located in a very small geographical area and the few factory owners were related or on generally friendly terms with each other. This enabled them to share orders, which meant that they could commit to large contracts that individual firms would have difficulty meeting. In 1805, for example, John Early secured a large order from the Hudson's Bay Company which he then shared with his fellow manufacturers.

Man warping threads onto a warp beam ready to put into a loom,

Witney, c1940s.

Witney manufacturers were not slow to take up new technology but this was not the whole story of their success. Their enterprising nature played a large part in their survival and success and their flexibility in adapting to the new industrial economy was just as important as their adoption of new equipment.

The 'Second Industrial Revolution'

Little development took place from about the 1870s until between the First and Second World Wars, when electrical power began to replace steam power. After the Second World War it became clear that the Witney blanket industry was going to have to modernise in order to keep up with increased competition from home and abroad. There were major developments, particularly at Early's, in the 1950s and 1960s which were so radical that they can be termed a 'Second Industrial Revolution'.

Weaver at Early's factory with a Sulzer loom, just before the

mill closed in 2002.

In 1963 Courtauld's, the textile and yarn manufacturers, acquired a share in of Early's and influence within the company. They brought new expertise into the industry, including the use of artificial fibres and German knitting machines for making blankets.

In 1965 Early's brought Fiberweaving, a new method of making textiles, from America. This increased output enormously, but once again the Witney manufacturers made efforts to find new markets and the effect on employment was small: the number of employees at Early's fell from 700 to 600 when the new machinery was introduced, but rose again soon after [15]. Smith and Philips' also used similar needlepunch technology as well as modernising their power looms. All these changes, however, could not stem the decline in the industry that set in throughout the 1970s. This caused Early's in particular to diversify their products, using the Fiberweavers for making a wide range of different products including fire blankets, sanitary towel linings and anti-static flooring tiles.

|